Hello everyone! Happy June! This week we read all about Indigenizing archaeology and incorporating Indigenous methodologies into archaeological theory and research designs. Particularly, the importance of place names to Indigenous cultures as a way of returning (Cowie & Teeman 2022). When Native American lands were settled, they were renamed in the colonizer’s language. The renaming of Indigenous lands also erased its Indigenous history in local memory, prioritizing European origins and history. This narrative portrays Indigenous peoples as distinctly separate from their land, colonial history, and contemporary people in the area. Native America has a continued tie to their ancestral lands. Physically returning ancestral Native American land to its peoples happens simultaneously with returning their Indigenous names, too. These are both forms of healing as spiritual importance and homeostasis is returned to the land (Cowie & Teeman 2022).

A large theme for this week is returning and healing. Archaeology plays an active role in healing, too. When an excavation is conducted and Native American cultural materials are found, they are removed and cataloged for further analysis in a lab. However, this collection erases evidence that Native American groups once inhabited their ancestral lands. This contributes even further to and can bring back painful memories of forced removal. As the authors (Cruz et al. 2022: 278) state, “If all the artifacts are removed from the landscape, then we have nothing to show we were ever there. That is why it is so important to leave archaeological materials, lithics, etc., in place. It is our story and we want to maintain that connection to the landscape. Nobody should have the right to erase history by the removal of material evidence.”

As archaeology continues to become more Indigenized, new methods for collection of Native American cultural material that mitigate this pain must be implemented (Downer 1997). This includes repatriating the remains of ancestors and ceremonial cultural material back to their cultural groups, reframing archaeological methods to incorporate Native American worldviews (Smith 1999), and recording artifacts in place. Recording artifacts in place involves taking pictures of, documenting the physical location of, sketching, and collecting any other necessary data from an artifact before redepositing it into the earth.

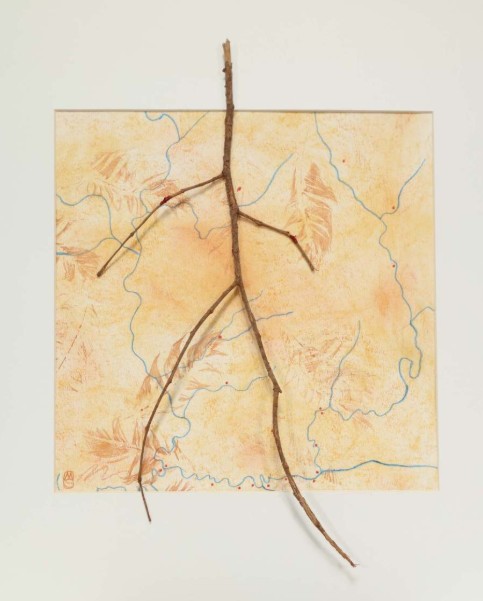

We also visited “This Land Calls Us Home: Indigenous Relationships with the Southeastern Homeland,” an art exhibit at Emory University’s Robert W. Woodruff Library that features 25 Native American artists, with over 50 pieces of art on display. This exhibit explores Southeastern Native American heritage through basket weaving, language, painting, jewelry, textiles, storytelling, film, and many more mediums. My favorite piece is by Melinda Schwakhofer (Mvskoke) titled Red Stick Leads Us Home. I was drawn to the light impressions of the feathers against the watercolor background, resembling a map. The map, ancestral lands, and history are being reclaimed. The title references the Red Stick warriors of the Upper Creek, who resisted European American settlement in their lands and fought in the Creek Civil War to return to traditional ways of life.

References Cited

Cowie, Sarah E. and Diane L. Teeman. 2022. Navigating Entanglements and Mitigating Intergenerational Trauma in Two Collaborative projects: Stewart Indian School and “Our Ancestors’ Walk of Sorrow” Forced Removal Trail. In Archaeologies of Indigenous Presence, edited by Tsim D. Schneider and Lee M. Panich, pp. 265-286.

Downer, Alan S. 1997. Archaeologists-Native American Relations. In Native Americans and Archaeologists: Stepping Stones to Common Ground, edited by Nina Swidler, Kurt E. Dongoske, Roger Anyon and Alan S. Downer, pp. 23-34.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999 Twenty-Five Indigenous Projects. In Decolonizing Methodologies, pp. 142-162. Zed Books, Ltd., London.