Welcome to New South’s space for celebrating Black heritage all year long. We invite you to explore this page to learn more about Black history and archaeology in the states where New South has offices: Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. You will also find a video about the importance of diversity in the cultural resource management industry and an excellent piece on Black history written by our own Velma Fann.

A Black History Story

by Velma Fann, New South Historian

My colleague, Patrick Sullivan, forwarded an email to the New South history staff with a link to the 1875 Voter Registration and Oath Books for counties in Alabama. My grandmother’s foreparents are from Dallas and Perry Counties, where they were enslaved by the Peeples, Shelton, and perhaps Handy, and Minter families.

The link piqued my interest. I looked in the Dallas County registration book for the town of Plantersville. The family church is there. Graves in the church cemetery date back to the early 1900s, interring those born in or just after slavery. My grandmother’s mother is buried there in an unmarked grave near the grove of trees along the property line.

In the Plantersville section of the book, I found surnames Peeples and Shelton. Long ago, my grandmother (now deceased) shared with me the names of her forefathers, but they were not among those persons listed. I started to give up my search, then decided to look at the registrations in Selma. Mine was a brief search, as to my knowledge, none of my family had lived there.

Selma was established as the county seat of Dallas in 1865, so I reasoned that my ancestors who lived nearby may have traveled there to register to vote. The section for Selma was lengthy, and the search was an eye strainer. And then I found them: Baily (Handy) Minter, my grandmother’s grandfather, and other relatives: Wyatt Minter, Peter Minter, and Burl (Burrell) Minter—all persons of whom my grandmother had spoken.

I paused when I read their names on the registration roll. I spoke their names out loud, then smiled. Researchers count it a relief, and yes, a blessing when they can document past relatives. The find is especially encouraging for African Americans. Our early lineage is often tucked away in records of the enslavers—wills, estate sales, deeds, and such. Occasionally our ancestors’ names appear in historic newspapers—in “runaway slave” notices placed by enslavers or “information wanted” notices placed by freedmen and women searching for loved ones sold away. African Americans, like other groups, hit a “wall” at times when researching the past. For us, it is a painful wall, one built by chattel slavery.

Finding the names of my ancestors, particularly as they were Black men, made me sit a little taller. Here they were in Dallas County, Alabama, 10 years after the Civil War and in the heat of Reconstruction, exercising their newly found right to vote. How long did they enjoy this right before Black Codes, poll taxes, literacy tests, and voter “qualification” questions restricted their freedom and ruled them ineligible or unfit to vote? Why is it that today, 127 years later, African Americans are still weighted down by voter suppression laws? Why, in 2022, are Historically Black Colleges and Universities receiving bomb threats? Why must Black parents still have “the talk” with their children, explaining what to do and not to do if stopped by law enforcement? Why have we come so far, and still have so far to go?

I needed to see my ancestors’ names. I needed to know that they, men formerly enslaved, dared to register to vote. I could hear them saying to me “Don’t give up the fight,” and assuring me in the words of the Negro Spiritual to “Hold on, just a little while longer. Everything will be alright.”

Thank you, Patrick, for sharing the link and to the Alabama Department of Archives and History for making the Voter Registration and Oath Books accessible on line. I will share this information with my son and remind him that we have been and always will be, voters.

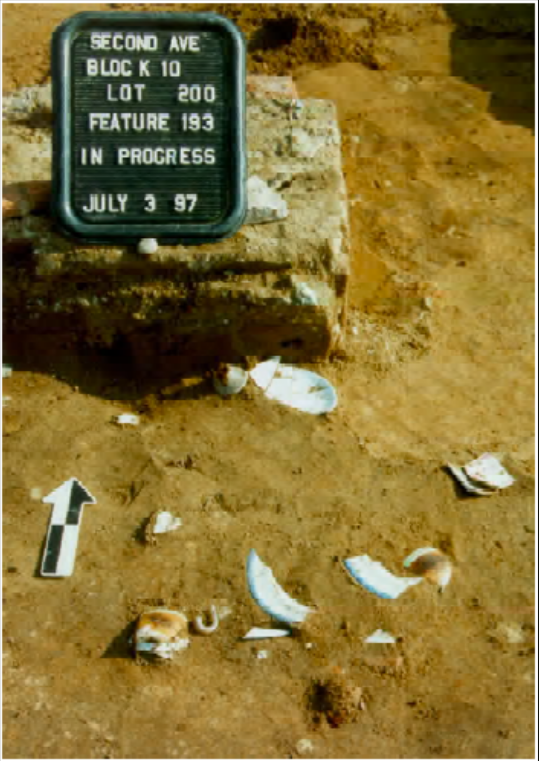

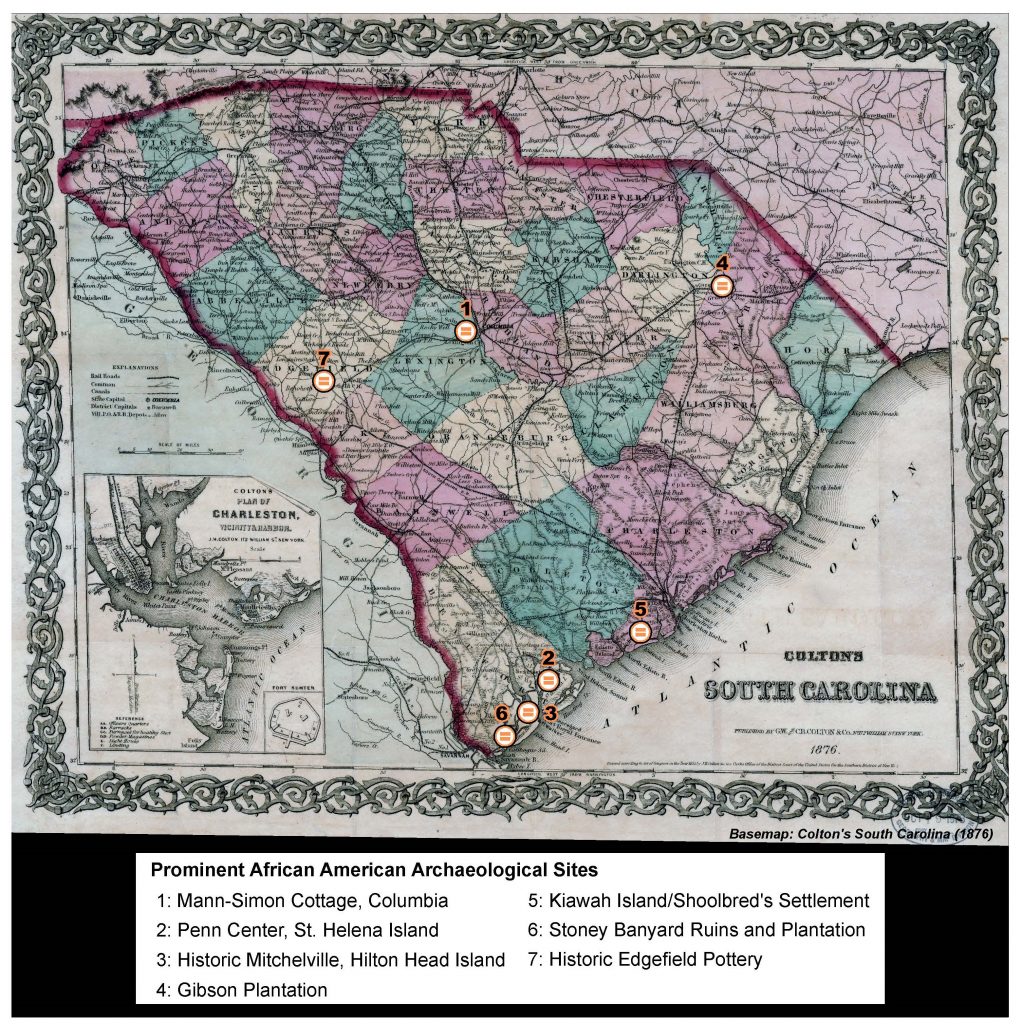

African American Archaeological Sites

The study of sites pertaining to Black history contributes to the awareness, education, and understanding of Black historic communities. In turn, we can better understand today’s Black communities and illuminate a brighter future for people of all backgrounds. Here we discuss a few of the archaeological sites representing Black heritage in Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia to show what is possible when researchers work with communities to excavate the truth that unites us.

Georgia

Albany

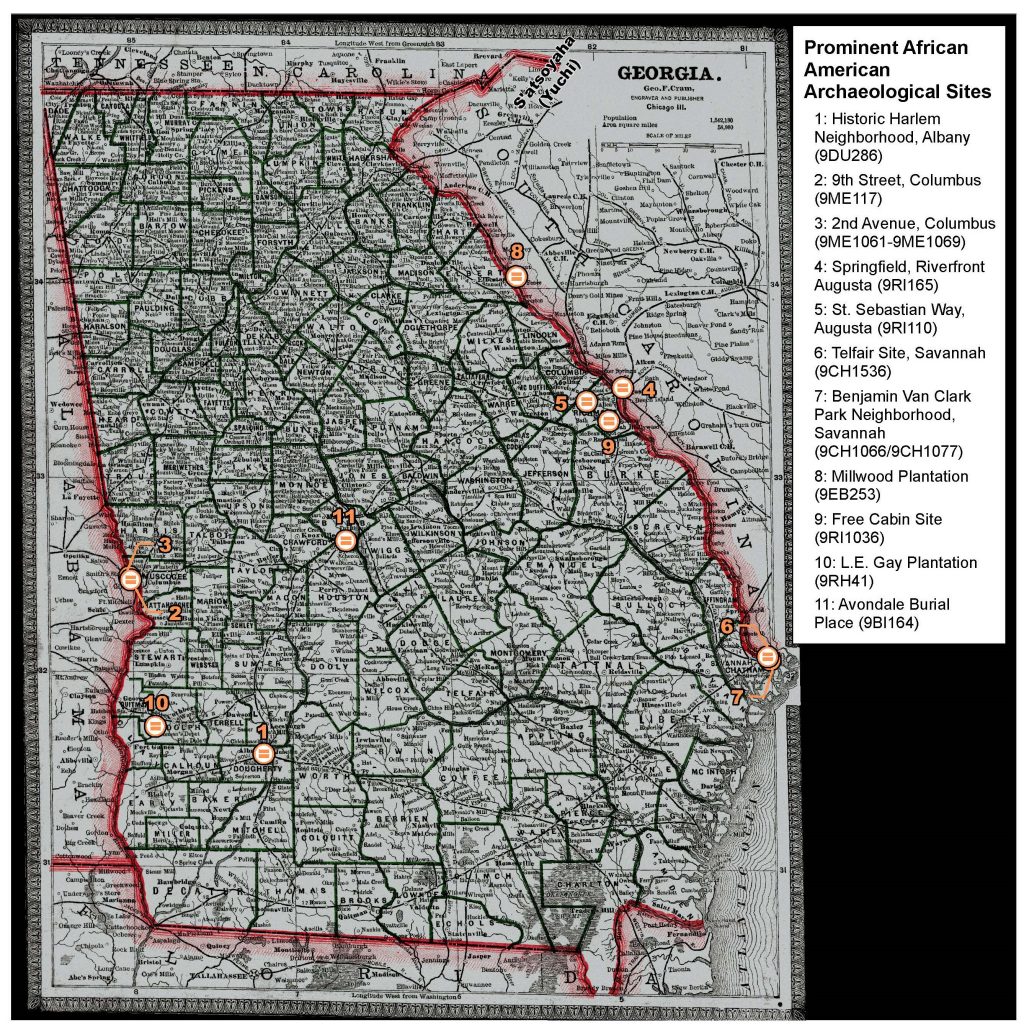

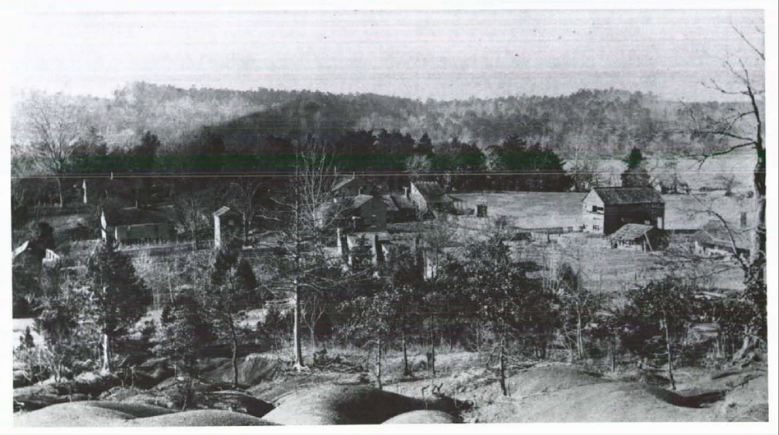

HISTORIC HARLEM NEIGHBORHOOD OF ALBANY, GA

Archaeology excavations have been conducted at Site 9DU286, a residential African American site within the historic Harlem Neighborhood of Downtown Albany. Archival research shows that at the time of the site’s occupation (ca. 1880–1950), the Harlem neighborhood consisted of an African American community populated by the freed people from nearby plantations and their descendants. The area remains a predominantly African American community today. The results of the excavations depict a community that valued self-expression and maintained ideals that elevated their social standing. You can download the full archaeology report and watch a video site tour at albanyunearthed.com.

Columbus

9TH STREET

Excavations at the 9th Street Block in Columbus identified deposits and features related to African American tenants. The site was initially occupied in circa 1840 by middle class white residents but by the early twentieth century the occupation was predominantly African American. Analyses of archaeological remains and historic sources were used to trace the evolution of Columbus from a frontier town to an urban community and from a white to a Black neighborhood.

Edgeware, and Other Ceramics, Southern Research, Living in Columbus Vol. I, 2005

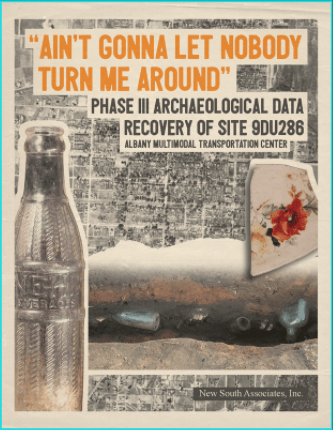

2ND AVENUE

The 2nd Avenue Revitalization Project, which also took place in Columbus, encompassed 10 city blocks in downtown. Research was focused on Black occupations dating from 1828 to 1869. The intersection of ethnicity and socioeconomic status was examined through the analysis of meat cuts to find that enslaved Black site inhabitants were resourceful and resilient.

The 9th Street Project was conducted by Southeastern Archaeological Services in 1997 and the 2nd Avenue Project was conducted by Southern Research in 2005.

Augusta

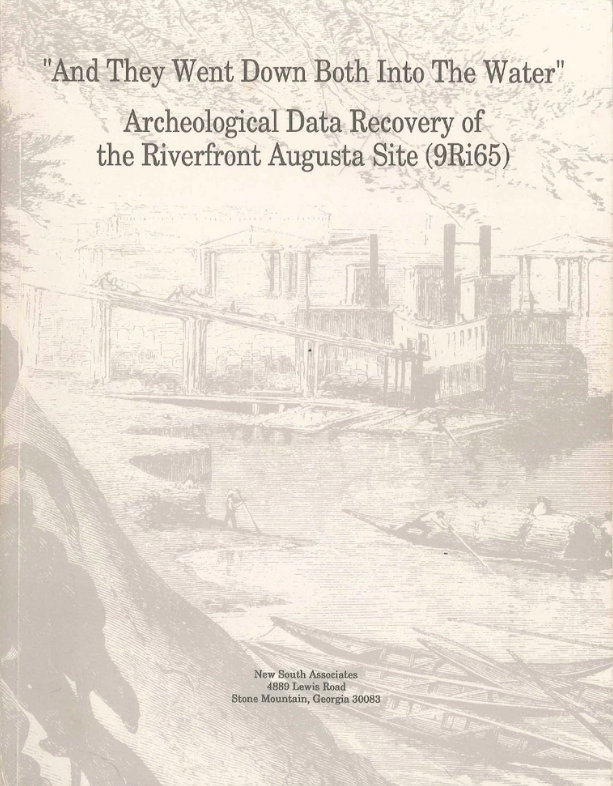

SPRINGFIED, RIVERFRONT

Excavations for the Riverfront Augusta Site identified pre– and post–Civil War deposits associated with the free African American community of Springfield. Archaeologists found a molded tobacco pipe modeled on archaeological finds from Nineveh that suggests the expression of hope for the end of slavery. They also learned that during the late 1800s, white upper class residents lived in areas with the highest elevations, while lower and middle class Black residents lived along sloped areas.

ST. SEBASTIAN WAY

Excavations were also conducted at St. Sebastian Way in Augusta. Researchers examined the cultural landscape to expand on the intersection of settlement patterns and ethnicity explored by the study of the Riverfront site. Researchers also found elevational differences in settlement patterns among white and Black residents. They also examined variation in architecture and lot sizes among Black and white residential areas. Black houses and lots were generally smaller than their white counterparts. These analyses demonstrated that residential development in the city was arranged to reinforce the prevailing racial relations at the turn of the twentieth century.

Savannah

BENJAMIN VAN CLARK PARK NEIGHBORHOOD

Archaeologists have conducted excavations at two sites within the Benjamin Van Clark Park Neighborhood of Savannah as well. Working-class African Americans occupied the sites from the mid-1800s through the mid-1900s. Artifacts suggest that these sites served as important locations within the neighborhood for Black community socializing.

TELFAIR SITE

Archaeological excavations have taken place at the Telfair Site, located centrally in Downtown Savannah, the Telfair Site is a contributing resource to the Savannah National Historic Landmark District dating from the 1700s through the 1900s. The Telfair Site, representing over 200 years of urban occupation, was inhabited by Black and white residents until the turn of the twentieth century when it became dominated by lower to middle class whites.

The Telfair Site project was conducted by the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in 1983 and the Benjamin Van Clark Park Neighborhood project was conducted by TRC in 2006.

Macon

AVONDALE BURIAL PLACE

The Avondale Burial Place is a long- forgotten Black cemetery in southern Bibb County, Georgia. Lacking tombstones, markers, or other signs of its existence, the cemetery was found by archaeologists during a survey of the area. An archaeological recovery and relocation of the deceased was conducted because construction would have otherwise destroyed it. Ground penetrating radar, search and rescue dogs, and excavation revealed 106 burials. Research indicated that the cemetery was created and used by an African American community during the 1800s and early 1900s. People buried at the cemetery probably included slaves, ex-slaves, and slave descendants who worked on antebellum and postbellum plantations and farms in the area.

Elbert County

MILLWOOD PLANTATION

An early study of tenancy in Georgia was conducted by Charles Orser in 1988 at the Millwood Plantation (ca. 1834–1925) in Elbert County. This study examined ways in which artifacts reflect social relations established by wage-labor systems. Researchers found that variation in socioeconomic status resulted from an uneven power and wealth distribution. Status was examined through the analysis of settlement patterns at the plantation. The size and layout of the owner’s house and the tenants’ houses shed light on the organization of labor and uneven distribution of wealth.

Richmond County

FREE CABIN SITE

An archaeological study has also been conducted at the Free Cabin site in Richmond County, Georgia. This tenant farm site (ca. 1870–1960) contained two African American tenant houses. Topics addressed in this study include socioeconomic status, self-sufficiency, consumption, and land use patterns. Analyses of features and artifacts indicated that the site inhabitants had a low socioeconomic status and relied heavily on practices of self-sufficiency. These findings were informed by archaeological evidence suggestive of consumption practices involving livestock, homegrown produce, and wild plants.

Randolph County

L.E. GAY PLANTATION

An archaeological study of the L.E. Gay Plantation (ca. 1880–1950) in Randolph County, Georgia involved the examination of an African American farm community. A cluster of five tenant houses was investigated to inform on land use, consumerism, socioeconomic status, diet, and ethnic identity. A combination of micro- and macro- analysis was employed by investigating the houses as individual entities and by examining the plantation as one component of a larger landscape. Findings related to land use indicated that agricultural features like cellars and hearths dominated the tenant house yards. Some tenants planted ornamental flowers such as daffodils and morning glories, while others focused only on food-bearing plants.

South Carolina

Columbia

MANN-SIMON SITE

The Mann-Simons Site in Downtown Columbia was originally constructed as a series of residential and commercial structures. After being freed from enslavement, Celia Mann and Ben Delane traveled from Charleston to Columbia, where Ben purchased the land containing the Mann-Simons cottage in 1843. Generations of their descendants lived in the same set of residences until 1970. These descendants owned numerous businesses at the site and participated in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Grassroots organization by descendants and locals led to the preservation of the only home site that remains, now a historic outdoor museum. Archaeological excavations performed by the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology and the Historic Columbia Foundation have revealed patterns in how site occupants lived during its 130-year continual occupation.

St. Helena Island

PENN CENTER

Penn Center, now a National Historic Landmark District, was founded in 1862 as a first-of-its-kind educational institution for Gullah Geechee freedmen and freedwomen living in coastal South Carolina. While early offerings included the teachings of reading and writing, the institution evolved into a focal point of the Gullah Geechee community which offered services for farming, blacksmithing, marketing, day care, and clinical services. The campus even served as a retreat for leaders of the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. Today the site serves as a pinnacle of preservation and cultural heritage for the Gullah Geechee people.

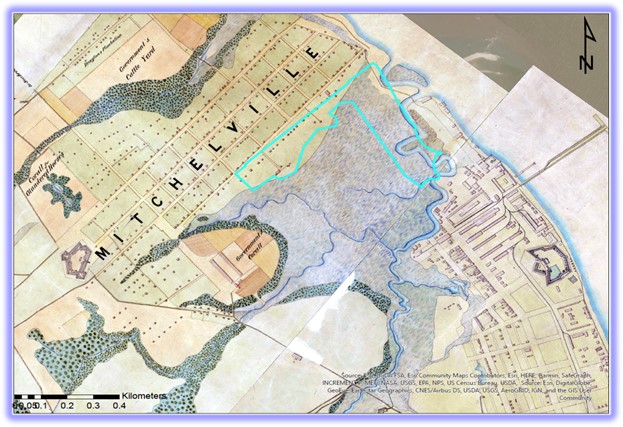

Hilton Head Island

HISTORIC MITCHELVILLE

Located on Hilton Head Island, SC, Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park is the remaining protected area of what was once Mitchelville, the first free Black town in the South. Mitchelville citizens were free before the Emancipation Proclamation and their experiences paved the way for newly free Black Americans. Mitchelville was comprised of refugees who had fled enslavement, making their way to Union lines during the Civil War. By November of 1862 Mitchelville residents were building their town on a gridded road system, building their houses on quarter-acre lots, and teaching themselves how to be democratic citizens. Mitchelville had the first compulsory school system in the state of SC, several churches, a dozen stores, a newspaper, a tattoo and ice cream parlor, its own police force, a grand hotel, and upwards of 3,000 citizens. The Historic Mitchelville Freedom Park is in the process of building a visitors center and museum where folks can come to learn about the remarkable residents who built Mitchelville.

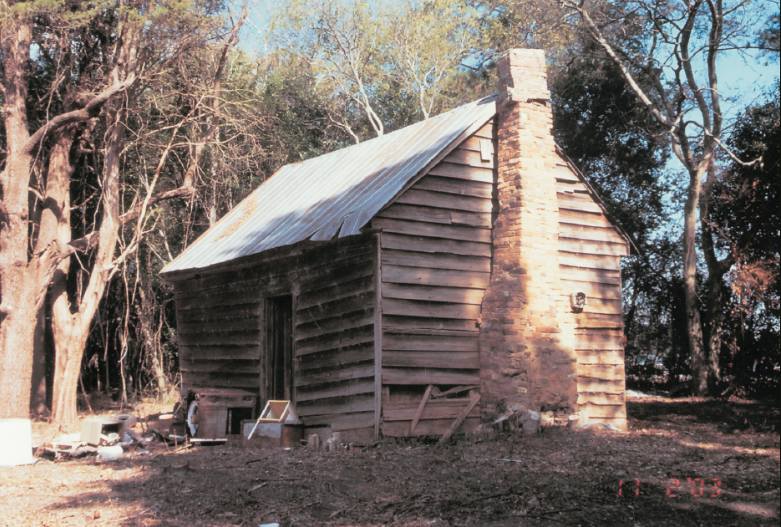

Mars Bluff

GIBSON PLANTATION

Multiple archaeological sites have been recorded at Gibson Plantation along the Pee Dee River, including Site 38FL240. This site is the remains of a complex of structures previously inhabited by the Black occupants who worked at the plantation from days of slavery and into the times of tenant farming. Archaeological excavations at 38FL240 examined the remains of three brick-foundation structures along with various landscape features. The site at the time of excavations boasted several types of ornamental shrubs and flowers still thriving 60 years after people had lived there. Archaeologists made particular note of the garden area which contained not only garden-related items, but children’s toys, clothes-washing items, and food preparation items. The artifacts found in this outdoor area, typically reflecting mundane activities, reveal how occupants spent their down time and put effort into enriching their lives through small acts of display.

Kiawah Island

SHOOLBRED’S OLD SETTLEMENT

Kiawah Island, south of Charleston, has been inhabited for more than 4,000 years. Historically, hundreds of enslaved Black people were brought to the very isolated island to labor in indigo and cotton fields. At Site 38CH123, Shoolbred’s Old Settlement, archaeologists have examined architectural changes, ceramic types and styles, and religious objects reflecting the lives of the enslaved Black people during their occupation on Kiawah Island.

Hilton Head Island

STONEY/BARNYARD PLANTATION

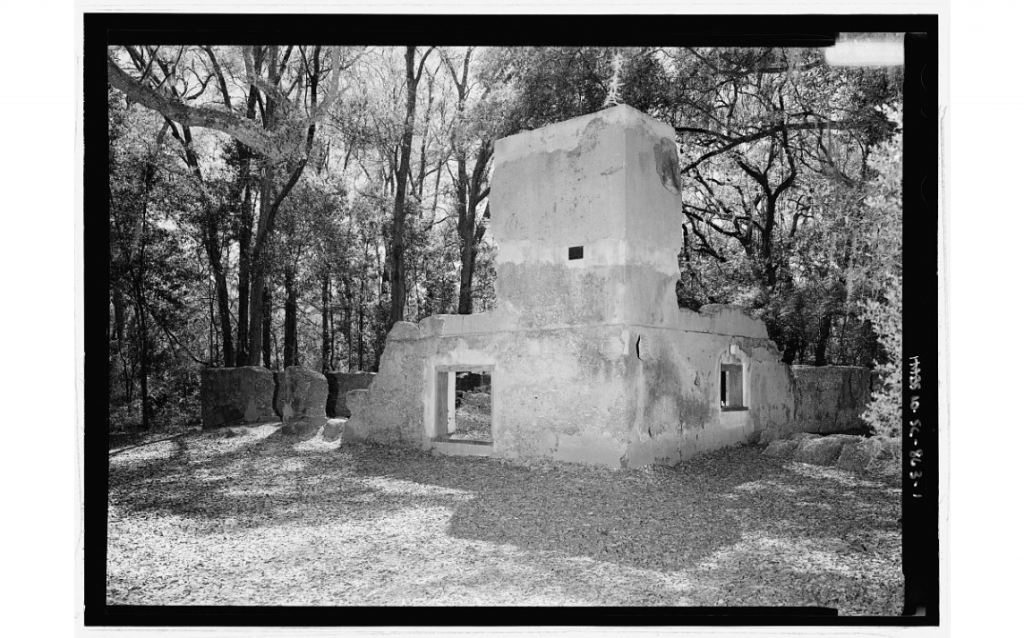

The Stoney/Baynard Plantation site, 38BU58, consists of large tabby ruins of a main plantation house and other associated structures including the quarters of the enslaved Black people working within the tabby house. In the early 1990s, archaeologists from the Chicora Foundation excavated and studied the site as it related to the enslaved population who worked at the residence in a very isolated part of the state. Among the many questions asked, the archaeologists sought to examine how landscape features and structure locations influenced the division of the white and Black populations, and how potential differences in the material culture and lifeways of those working in the plantation house versus those who labored in agricultural fields.

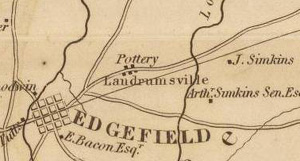

Edgefield

HISTORIC EDGEFIELD POTTERY

The town of Edgefield became an epicenter of alkaline-glazed stoneware pottery in North America in the early 19th century. The driving force of this mass-scale production were enslaved Black laborers skilled in pottery production. Most notable was David Drake, or Dave the Potter, whose work was considered to be of exceptional artistry. While Dave the Potter may be the most well-known, numerous other enslaved Black laborers produced quality wares of the Edgefield tradition. Face vessels, or face jugs, were very popular in the area and were influenced by traditional West Central African styles. Archaeological excavations by Dr. Chris Fennell (University of Illinois) and his students have examined the landscape, architecture, and personal aspects of this early pottery-making tradition.

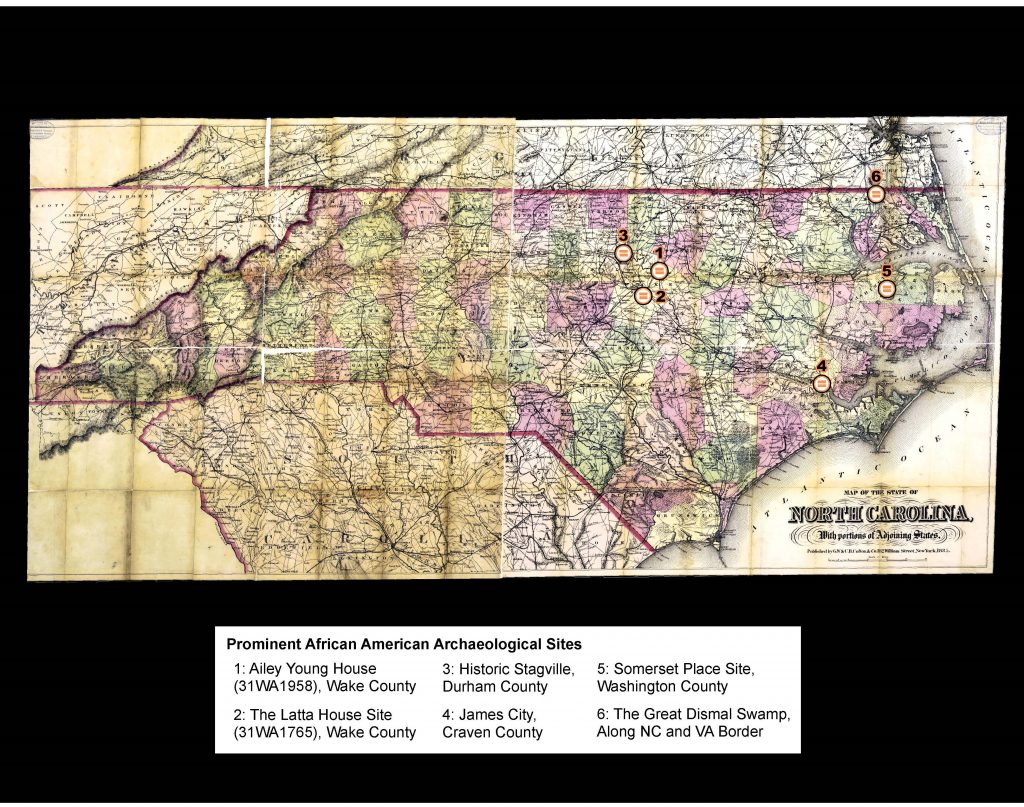

North Carolina

Wake County

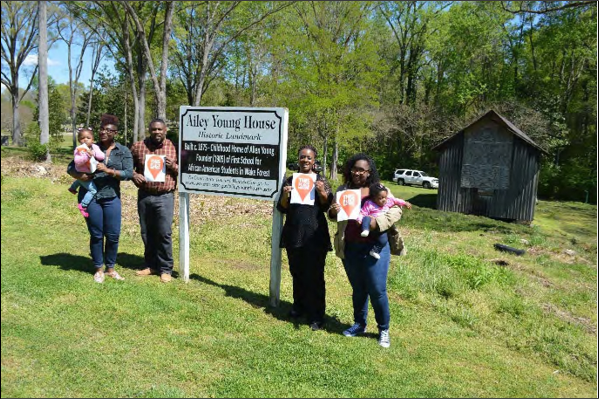

AILEY YOUNG HOUSE

Archaeology excavations have been conducted at Site 31WA1958, a residential African American Site in Wake Forest, Wake County, North Carolina. The Ailey Young House was built circa 1875 and was one of several rental properties along “Simmons Row.” The house was occupied by the Young family since its construction and the house is a rare example of a standing, saddlebag duplex. Ground-penetrating radar and metal detection survey identified a porch and possible root cellar along with activities areas near the house.

THE REV. M. L. LATTA HOUSE SITE

Excavations were conducted at Site 31WA1765 following a 2007 fire that burnt the house to the ground. The houses namesake, Rev. Morgan L. Latta was the founder of Latta University in the historically Black neighborhood of Oberlin Village in Raleigh, North Carolina. Latta was born into enslavement in 1853 in Durham County. The archaeological survey determined that the site contained intact archaeological deposits that were concentrated in the western half of the property.

Durham County

HISTORIC STAGVILLE

Historic Stagville is a large plantation in Durham County that was owned by the Bennehan-Cameron family, who had enslaved over 900 people. The site contains four original “slave dwellings” along with a barn and the Bennehan-Cameron house. The “slave dwellings” date to 1851 and have been the subject of multiple archaeological investigations. As a result of the excavations, archaeologists have been able to determine that the “slave cabins” post-date 1820.

Craven County

JAMES CITY

James City, originally the Trent River Settlement, was founded as a Black settlement during the Civil War following the Union occupation of nearby New Bern. The settlement was the largest refuge for Black men and women in North Carolina during the Civil War. The township became a residential hub during the Reconstruction Era but was eventually met with hostility from the white family that owned the land where James City was located. Through the help of several local organizations, the city has preserved its history and heritage through several initiatives including archaeological excavations.

Washington County

SOMERSET PLACE

Somerset Place is a large nineteenth-century plantation in Washington County, North Carolina that was operated by the Collins family from 1785 to 1865. Over 800 enslaved people lived on the property during its years of operation. The plantation produced lumber, rice, corn, oats, wheat, and numerous other crops. Archaeological excavation has occurred at several buildings on the property including the Plantation Hospital and the “Large Slave Quarter.” The plantation encompassed over 50 structures, including a boarding school for the Collins children, a church, and 26 dwellings for enslaved people and employees of the family such as tutors and ministers.

The Great Dismal Swamp

The Great Dismal Swamp, located along the North Carolina and Virginia border, was home to numerous African American refugee, or “marronage” camps. The hostile environment and sheer enormity of the swamp made it the perfect place for those fleeing enslavement to live. From 1680 through the Civil War, the Great Dismal Swamp was occupied by thousands of African Americans who had escaped enslavement. These communities ultimately disbanded once slavery was abolished. Since 2002, the swamp has been the subject of archaeological investigation to better understand the lives of those who occupied the swamp.

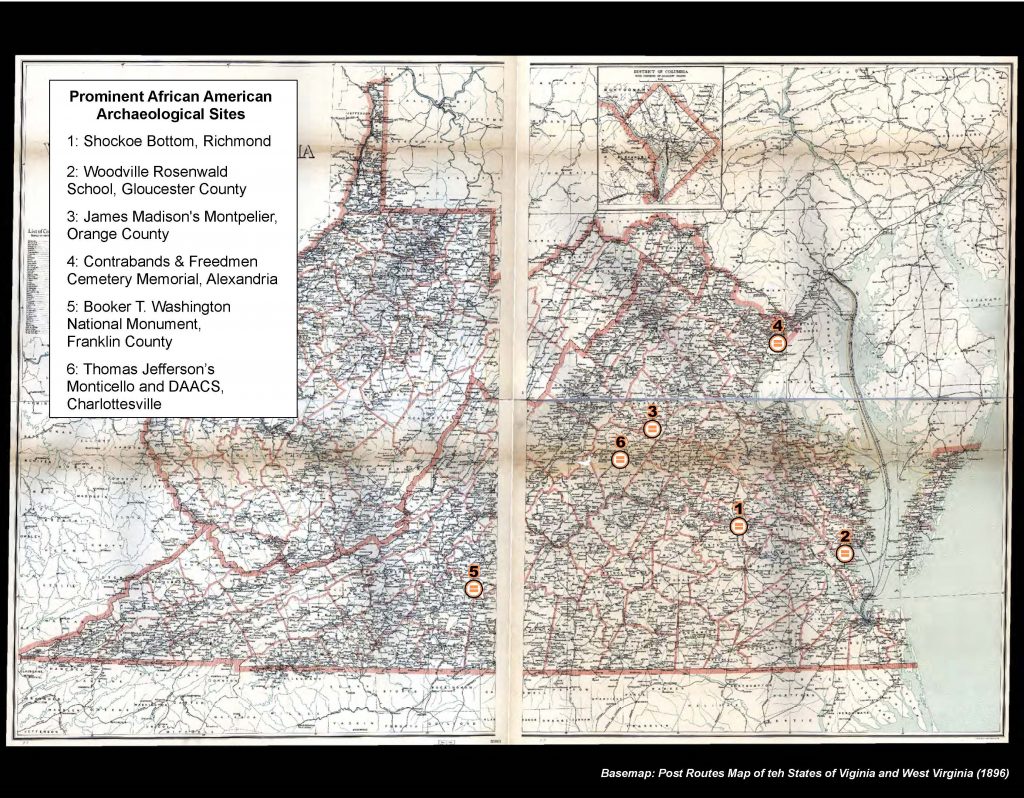

Virginia

Richmond

SHOCKOE BOTTOM

Shockoe Bottom was the center of Richmond’s slave trade and was a crucial site in the nation’s interstate slave trade. Second only in importance to New Orleans in the last half of the century, Shockhoe Bottom was once populated with slave-trade auction houses, offices, slave jails, and residences of the most prominent slave traders.

Much of the physical remains of Shockoe Bottom have since been destroyed and its history often overlooked. Shockoe Bottom, however, remains a sacred location for many in the descendant community and serves as a reminder of the suffering and injustice caused by slavery and the resistance to it.

Mayor Levar Stoney and the City Council made plans in 2017 to build an interpretative center that remembers the devastation Shockoe Bottom caused African Americans.

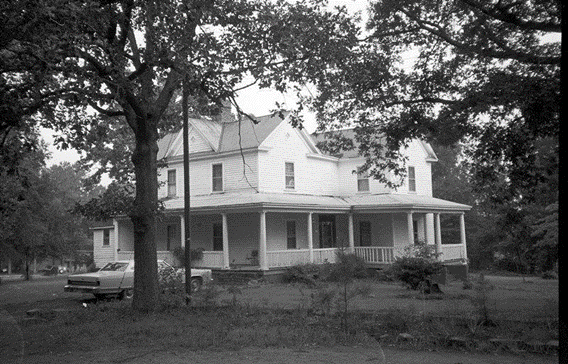

Gloucester

WOODVILLE ROSENWALD SCHOOL

The Woodville School is located on Route 17 in Gloucester, Virginia. It is one of the few remaining Rosenwald Schools built across the south for African American children in the first half of the 20th century. From the Woodville Rosenwald School Foundation: “Julius Rosenwald, CEO of Sears, Roebuck & Co., funded 5300 elementary and training schools in partnership with local communities. In 1919, T.C. Walker, the first African American lawyer in Gloucester County, traveled to Chicago to meet with Rosenwald and secured funding for six schools and a teachers’ home. Rosenwald required the community to contribute half of the cost, in money, materials or labor, and he contributed the rest. Only 800 Rosenwald schools remain and, of those built in Gloucester, only the Woodville School remains. The Woodville School is listed on the National and Virginia State Historic Registries.”

A community archaeology program was established to continue discovering and preserving the educational history of Gloucester County’s African American community.

Orange County

MONTPELIER AND THE MONTPELIER DESCENDANTS COMMITTEE (MDC)

The historic home and grounds of James and Dolley Madison serves as a museum to the fourth President of the United States as well as interprets the lives of the enslaved community and their descendants’ struggle for freedom and equal rights. Montpelier features one of the largest archaeological research projects on the study of slavery.

Interpretation of Montpelier’s history is an exercise in developing structural parity between The Montpelier Foundation and the Montpelier Descendants Committee (MDC). The MDC is a descendant-led organization that established itself as an equal co-steward of the site in 2021. From the MDC: “The MDC is devoted to restoring the narratives of enslaved Americans at plantation sites in Central Virginia, including but not limited to James Madison’s Montpelier, from the margins to the center of historical discourse. The MDC promotes a more accurate understanding of the lives of enslaved people based on broader, richer and more truthful interpretations of American history.’ Together, The Montpelier Foundation and The MDC have potentially created an inclusive power-sharing framework for all historic sites interpreting the institution of slavery and its legacy.”

Alexandria

CONTRABANDS & FREEDMEN CEMETERY MEMORIAL

From the Alexandria City government: “The Alexandria Contrabands & Freedmen Cemetery served as the burial place for about 1,800 African Americans who fled to Alexandria to escape from bondage during the Civil War. A Memorial opened in 2014 on the site of the cemetery, to honor the memory of the Freedmen, the hardships they faced, and their contributions to the City.”

Franklin County

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON NATIONAL MONUMENT

Booker T. Washington was born in April 1856 on the Burroughs Plantation in Franklin County, Virginia. He became a noted educator, orator, author and advisor to U.S. presidents. Washington included a retelling of his birth and recollections from the first nine years of his life living as an enslaved individual on the tobacco plantation in his autobiography, Up From Slavery.

From the National Park Service: “The park’s interpretive goals are …to preserve and protect the birthsite of Booker T. Washington, its cultural landscape and viewshed; To memorialize and interpret Booker T. Washington’s life, historical contributions, accomplishments, and significant role in American history; To provide a focal point for continuing discussions about the legacy of Booker T. Washington and the evolving context of race in American society; and to provide a resource to educate the public on the life and achievements of Booker T. Washington.”

Archaeological surveys continue to explore the remains of the Booker T. Washington National Monument. In fact, New South Associates recently performed a geophysical survey within the historic district last year!

Charlottesville

MONTICELLO AND THE DIGITAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL ARCHIVE OF COMPARATIVE SLAVERY (DAACS)

Most people have heard of, or even visited, Thomas Jefferson’s home in Charlottesville, Virginia. The third President of the United States enslaved over 400 individuals to work on the 5,000 acre plantation. Today, visitors are able to tour the house, grounds, and gardens and learn about the Jeffersons, the individuals and families enslaved at Monticello, and the inherent contradiction of creating the Declaration of Independence in such an environment. But did you know that Monticello is also the home of the Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery (most commonly referred to as DAACS)?

DAACS is a unique community resource that allows archaeologists, historians, research institutes, or any other interested parties to learn more about the histories of the enslaved communities throughout the Atlantic. The web-based archive allows for inter-site research on slavery throughout the Chesapeake, Carolinas, and the Caribbean. DAACS’ goal is to “help scholars from different disciplines use archaeological evidence to advance our historical understanding of the slave-based society that evolved in the Atlantic World during the colonial and ante-bellum periods.”

Tennessee’s Landscape of Liberation Project

LANDSCAPE OF LIBERATION: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN GEOGRAPHY OF TENNESSEE

The Tennessee State Library & Archives, Fullerton Geospatial Lab at Middle Tennessee State University, State of Tennessee STS-GIS, and Tennessee State Museum collaborated to create a website that educates about the landscape of emancipation as is unfolded from 1860 to 1890. This project was funded with a grant from the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area. The website features an interactive map which visitors can use to explore that landscape. Every point on the map is linked to primary documents and images that tell the story of people, places, and events.

This mapping application serves as a valuable tool for looking at this transformative time of profound social change. Most importantly, the enlistment and service of African American soldiers in Tennessee provided an irrefutable case for freedom and the most compelling evidence that slavery was coming to an end.

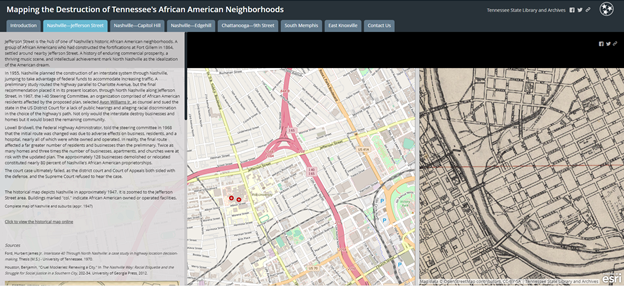

MAPPING THE DESTRUCTION OF TENNESSEE’S AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORHOODS STORYMAP

This Storymap, available on the Landscape of Liberation website, details the often destructive impact of mid-20th century urban renewal and interstate highway projects on Tennessee’s African American communities.

This project combines GIS software, historical maps, and other archival sources to create an interactive exhibit. Users can visualize the historical landscape and see direct effects of these public works projects in Chattanooga, Knoxville, Memphis, and Nashville.

References

Adams, Natalie P., Debi Hacker, and Michael Trinkley. 1995. In the Shadow of the Big House: Domestic Slaves at Stoney/Baynard Plantation, Hilton Head Island. Research Series 40. Columbia, South Carolina: Chicora Foundation.

Adams, Natalie P., Mark T. Swanson, J.W. Joseph, Leslie Raymer, and Lisa D. O’Steen. 2005. “The Free Cabin Site (9RT1036): Archaeological Examination of a Postbellum Tenant Occupation Near Hepzibah, Richmond County, Georgia.” Report Prepared for GDOT and Earth Tech, Atlanta, Georgia. Stone Mountain, Georgia: Report available from New South Associates, Inc.

Botwick, Bradford, and Staci Richey. 2010. “Archaeological Data Recovery of Site 9RI1110, St. Sebastian Way Expansion Project, City of Augusta, Richmond County, Georgia.” Stone Mountain, Georgia: New South Associates, Inc.

Calfas, George, Chris Fennell, Brooke Kenline, and Carl Steen. 2011. “Archaeological Investigation, LiDAR Aerial Survey, and Compositional Analysis of the Pottery in Edgefield, South Carolina.” South Carolina Antiquities 43: 33–39.

Dorland, M. Anne, Leslie Branch-Raymer, Linda Scott Cummings, Stefanie M. Smith, and Velma Thomas Fann. 2021. “‘Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around’: Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery of Site 9DU286, Albany Multimodal Transportation Center.” City of Albany, Dougherty County: New South Associates, Inc. prepared for Niles Bolton Associates for the Federal Transit Administration and Georgia Department of Transportation.

Elliott, Rita Folse. 2005. “Living in Columbus, Georgia 1828-1869: The Lives of Creeks, Traders, Enslaved African-Americans, Mill Operatives and Others As Told to Archaeologists.” 3235. Second Avenue Revitalization Project Series, Volume V. Savannah, GA: Southern Research. Athens, GA. Georgia Archaeological Site File.

Honerkamp, Nicholas R, Bruce R. Council, and Charles H. Fairbanks. 1983. “The Reality of the City: Urban Archaeology at the Telfair Site, Savannah, Georgia.” Report Prepared for the National Park Service. Chattanooga, Tennessee: Jeffrey L. Brown Institute of Archaeology, University of Tennessee.

Joseph, J.W. 1993. “And They Went Down Both Into the Water”: Archaeological Data Recovery of the Riverfront Augusta Site (9Ri165). Stone Mountain, Georgia: New South Associates, Inc.

Ledbetter, Jerald R., John Lupold, and Lisa D. O’Steen. 1997. “Data Recovery at the Proposed Public Safety Complex, Columbus, Georgia.” CRM. Athens, Georgia: Southeastern Archaeological Services, Inc.

Matternes, Hugh B., Valerie S. Davis, Julie Coco, Staci Richey, and Sarah M. Lowry. 2012. “Hold Your Light on Canaan’s Shore: A Historical and Archaeological Investigation of the Avondale Burial Place (9BI164).” Technical Report No. 2097. Stone Mountain, Georgia: New South Associates, Inc.

Orser, Charles E. Jr., Annette M. Nedola, and James L. Roark. 1987. “Exploring the Rustic Life: Multidisciplinary Research at Millwood Plantation, A Large Piedmont Plantation in Abbeville County, South Carolina, and Elbert County, Georgia.” Chicago, Illinois: Report available from Mid-American Research Center, Loyola University of Chicago.

Reed, Mary Beth, Natalie Adams, Jennifer Azzarello, Terri Lotti, and Sharman Southall. 2011. “We Made A Day: History and Archaeology of Tenancy on the L.E. Gay Plantation, Randolph County, Georgia.” Report prepared for the Georgia Department of Transportation, Atlanta. Stone Mountain, Georgia: New South Associates, Inc.

Seibel, Scott, and Terri Russ. 2009. “An Intensive Cultural Resource Investigation: The Reverend M.L. Latta House and Latta University Site.” Wake County, NC: Report prepared by Environmental Services, Inc. for the Raliegh Historic Districts Commission and the City of Raleigh.

Steen, Carl. 2010. “Cultural Resources Investigations at Penn Center.” Columbia, South Carolina: Diachronic Research Foundation.

Thomas, Brian W., Sean Norris, Jeffrey L. Holland, and Dawn Reid. 2006. “Phase III Archaeological Data Recovery of Sites 9CH1066 and 9CH1067 within the Benjamin Van Clark Park Neighborhood, Savannah, Georgia.” 8339. Savannah, Geogia: Report Prepared by TRC for the Housing Authority of Savannah.

Town of Wake Forest. 2014. “Ailey Young House Historic Preservation Plan.”

Trinkley, Michael, and Natalie Adams. 1992. “Archaeological, Historical, and Architectural Survey of the Gibson Plantation Tract, Florence County, South Carolina.” Columbia, South Carolina: Chicora Foundation.

Trinkley, Michael, and Debi Hacker. 2009. “Shoolbred’s Old Settlement: Excavations at 38CH123, Kiawah Island, Charleston County, South Carolina.” 70. Chicora Foundation Research Series. Columbia, South Carolina: Chicora Foundation, Inc.