Subsistence studies are specialized analyses that address the relationship between people of the past and the plants and animals that they rely on for food, medicine, companionship, and more. Subsistence studies can be split into two specialties: Zooarchaeology and Ethnobotany (also known as Archaeobotany).

Zooarchaeologists (sometimes called faunal analysts) study the role of animals in the archaeological record. To do this, zooarchaeologists combine historical and ecological research with the analysis of animal bones and invertebrate shells (faunal remains) that are recovered during archaeological excavations via screening or flotation (see below for more information on this recovery method). Bones and shells can provide answers to questions about what people were eating when they occupied a particular site, how they gained access to food, what the environment looked like at the time, and whether domesticated animals were part of the community.

But how do zooarchaeologists know what kind of bones or shells they are looking at? To help with the identification process, zooarchaeologists consult a variety of sources including identification manuals, online databases, and comparative specimens. To start developing your identification skills, visit BoneID.net to see a variety of bone types. For fish bone identification, visit The Florida Museum of Natural History’s Pictorial Skeletal Atlas of Fishes.

Zooarchaeology Activities:

Natural History museums across the country are full of osteological collections and educational exhibits. One museum in particular, Skeletons: The Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma City, offers a publicly accessible list of educational activities for students of all ages. Their website hosts a list of activities that cater to everyone from Pre-K through college. Check out their Educational Programs page and choose an activity to complete. Use social media to tell us which is your favorite and don’t forget to tag #protectorsofthepast when you share!

Ethnobotanists study bits of plant material that remain in the soil long after a site is no longer occupied. In both prehistoric and historic communities, people have used plants as food, medicine, and to decorate personal spaces. The plant remains that ethnobotanists study most often consist of seeds and nut shells. However, sometimes ethnobotanists also have the opportunity to study the microscopic remains of plants including pollen spores and phytoliths (silica structures that are found in plant tissues). By identifying the plant types that are present in an archaeological assemblage, ethnobotanists can address questions regarding food, medicine, and the environment.

But how do ethnobotanists find evidence of plants, you ask? Check out the video Archaeobotany: The Black, Burned Bits of Prehistory from the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center to learn more about archaeobotany and how it works. If you are interested in learning more about seed identification, there are a number of books, manuals, and databases available. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has a searchable seed image database available for public access here.

To learn even more about zooarchaeology and Archaeobotany, watch New South’s Subsistence Studies videos with Zooarchaeologist Stefanie M. Smith and Archaeobotanist Lauren Walls below:

Flotation is a common method for both zooarchaeologists and ethnobotanists to collect material for analysis. Simply put, flotation is the process by which organic and inorganic material is removed from large samples of soil using water and mesh screen. During this process, the lighter organic material will float and can be skimmed from the surface. If you are interested in flotation and want to learn more, check out this blog post from the Digging for Bones Blog all about its history and purpose.

Often, zooarchaeologists and ethnobotanists work together to form a more complete picture of life in the archaeological record. By comparing and contrasting zooarchaeological and ethnobotanical data, it is possible to reconstruct environments and ecosystems that disappeared long ago. When these data sets are then compared with artifact and mapping data, a complete picture of life at a site begins to come together. Archaeology is truly a multi-disciplinary science.

Activity:

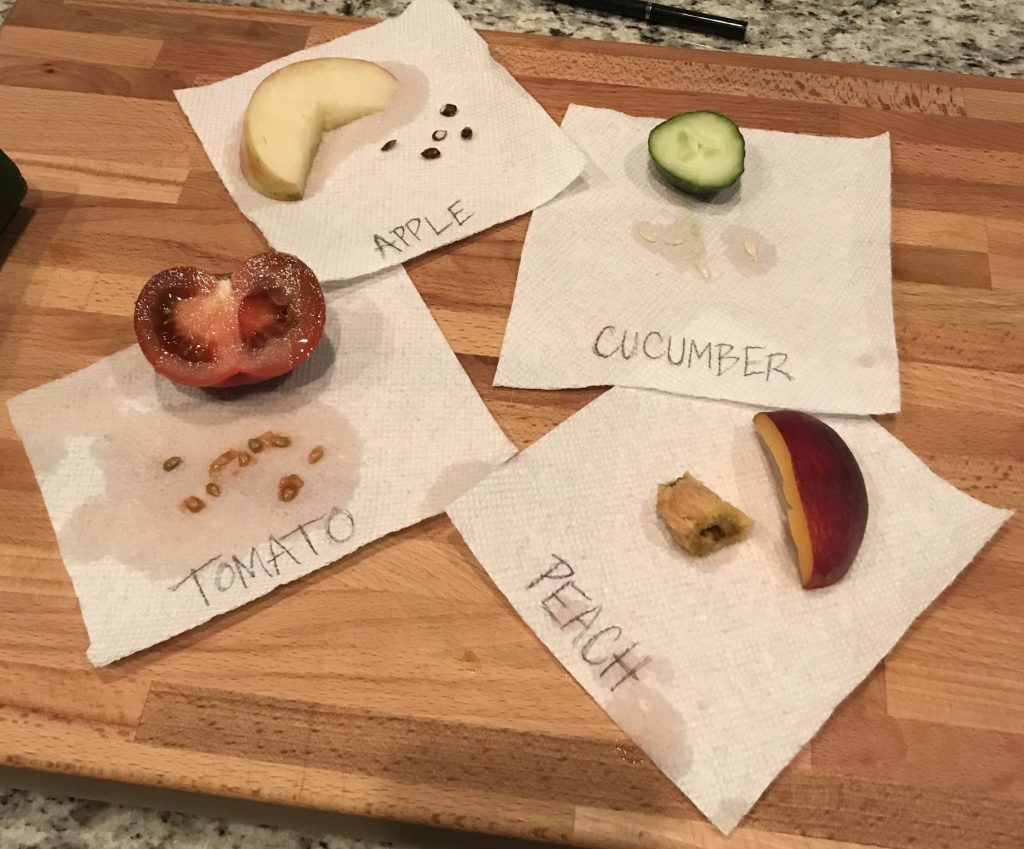

Are you ready to analyze some seeds? In this activity, you will use your observational skills to identify seeds and their associated plants. Maybe you can enjoy a snack while you work! For this activity, you’ll need an adult to help you out.

Materials:

- A variety of fruits and vegetables that contain seeds (at least 3 to 5 individual types such as strawberries, apples, squash, avocado, etc.)

- Napkins or paper towels

- Scissors

- Cutting board

- Kitchen knife

- Writing utensil

- Colored Pencils/Crayons (Optional)

- Ruler

- Notebook paper

- Birdseed (Optional for advanced extension)

- Paper plate (Optional for advanced extension)

- Toothpick (Optional for advanced extension)

Instructions:

- Rinse and dry your produce.

- Cut your napkin or paper towel into small squares (roughly 4×4 inches)

- Lay out each piece of produce and discuss what you see. Describe the shape, color, and size of each item.

- To keep a record of your observations, draw each piece of produce and label it on your notebook paper. Note whether the seeds are on the outside or the inside of each item.

- Next, carefully remove some of the seeds and place them on one of your paper towel squares. Label the square with the name of the fruit or vegetable. NOTE* An adult should help you with this step if your produce needs to be cut open.

- Record your observations of the seeds on your notebook paper. Describe their color, shape, texture, and measure the width and length of at least one seed. Draw the seeds beside your drawing of the corresponding fruit or vegetable.

- Repeat steps 4 through 6 with each piece of produce.

- When you have removed seeds and recorded your observations about each piece of produce, answer the discussion questions below.

Extension – If you enjoyed that activity and want to learn more, follow these steps to test your seed knowledge!

- Pour a small amount of birdseed onto a paper plate (1 or 2 tablespoons is plenty).

- Sort the seeds into piles by type. Do you see any seeds that you recognize? Label them on the plate.

- For those seeds that you do not recognize, use the internet and/or seed identification manuals, see if you can identify them. Confirm that you correctly identified the seeds that you originally recognized.

Discussion Questions:

- Do all fruits and vegetables contain seeds? Explain how the size and shape of a fruit or vegetable informs on the characteristics of its seeds.

- Analyze your observations to identify patterns. Were there any fruits or vegetables that could be grouped together based on similar characteristics?

- Compare the bird seed with fresh produce seeds. Do any seeds from the birdseed mix look familiar to you? If so, how? Explain what they tell you about the types of plants that birds can consume.

- When ethnobotanists sort material into groups, what are some characteristics that they should look for to help inform their sorting?

- Discuss how ethnobotanical materials end up at archaeological sites. What areas of a site might contain the most ethnobotanical material and why?

- Discuss the types of information that can be gained from the identification of ethnobotanical materials from archaeological sites. Why is this information important to our understanding of the past?

| Grade Level | Standard | Description |

| Kindergarten | SKL2 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to compare the similarities and differences in groups of organisms. a. Construct an argument supported by evidence for how animals can be grouped according to their features. b. Construct an argument supported by evidence for how plants can be grouped according to their features. |

| 5th | S5L1 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to group organisms using scientific classification procedures. a. Develop a model that illustrates how animals are sorted into groups (vertebrate and invertebrate) and how vertebrates are sorted into groups (fish, amphibian, reptile, bird, and mammal) using data from multiple sources. b. Develop a model that illustrates how plants are sorted into groups (seed producers, non-seed producers) using data from multiple sources. |

| 7th | S7L1 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to investigate the diversity of living organisms and how they can be compared scientifically. a. Develop and defend a model that categorizes organisms based on common characteristics. |

| 7th | S7L4 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to examine the interdependence of organisms with one another and their environments.c. Analyze and interpret data to provide evidence for how resource availability, disease, climate, and human activity affect individual organisms, populations, communities, and ecosystems. |

| 9-12 | SBO3 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to describe Georgia’s major physiographic ecoregions, their representative natural plant communities, and their conservation. |

| 9-12 | SBO6 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to analyze the economic and ecological importance of plants in human society. |

| 9-12 | SEC3 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to construct explanations of community interactions. |

| 9-12 | SZ1 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to derive the phylogeny of animal taxa using informative characteristics. |

| 9-12 | SZ3 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to compare and contrast structure and function of morphological and genetic characteristics across representative taxa. |

| 9-12 | SZ5 | Obtain, evaluate, and communicate information to analyze the relationship between humans and animals within various phyla. |

These standards of excellence were sourced from the Georgia Department of Education web page at https://www.georgiastandards.org/Georgia-Standards/Pages/default.aspx